Shoring up shipowners – what are taxpayers and employees getting in return for state aid under Covid-19?

10 November 2020

Governments around the world have been putting taxpayers' money into maritime as a way of shielding the strategic sector and its workers from some of the financial impact of Covid-19. Yet is their no-strings-attached approach to providing support for shipping companies the right way to go? Rob Coston takes a look at a new report

The International Transport Forum, an OECD think tank with 62 member countries, has released a new Covid-19 Transport Brief, subtitled 'Lessons from Covid-19 State Support for Maritime Shipping'.

The report is a snapshot of efforts to prop up parts of the industry during the Covid-19 economic crisis with financial support – efforts which are not currently linking ongoing support with issues such as flags of convenience and decarbonisation. It also offers advice for governments when determining future support.

Where is the support going?

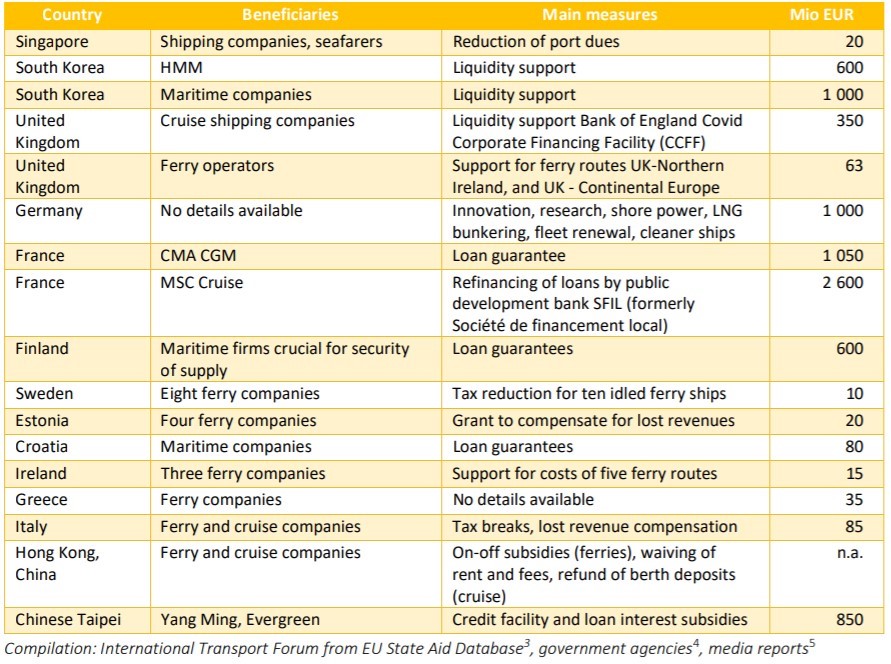

Shipping businesses have been able to take advantage of a wide variety of schemes created by governments to support all kinds of businesses. In addition to this, the International Transport Forum report identifies 13 countries that have implemented support specifically aimed at the shipping sector. This is probably an underestimate, however.

Some countries give support to the entire industry; others restrict their funding to particular sectors. While cargo shipping has been affected by a lower demand for products during the crisis, receiving state aid in France, South Korea and Taiwan, nine of the 17 known aid packages given to the shipping industry are going to ferry and cruise ship companies, which have been hit particularly hard by restrictions on movement across borders and even within individual countries.

Ferry services, which are an important lifeline for some citizens, have received support in the UK, Finland, Estonia, Greece, Italy and Sweden while cruise companies are covered in the UK, France and Hong Kong, with Germany looking to get involved too.

Flags of convenience mean that many large shipping businesses – in the cruise sector, for example – have made significant profits over the past decade without shouldering the tax burden. Covid-19 state aid is now going to these companies, often through less visible routes

What form does the support take?

As might be expected, countries are using a range of approaches to support maritime. For a start, some countries are being far more generous than others.

The form that the state aid takes is also varied. It ranges from tax exemptions and waived port fees to direct grants and compensation for idle vessels. There are also loan guarantees and cash from state-owned banks, much of which is going to 'very large shipping companies with high levels of debt acquired before Covid-19,' according to the report.

The report also warns that although four of the largest container companies have received state help, they also benefit from 'shadow subsidies' by cancelling planned sailings. This artificially reduced capacity has driven up prices, meaning that some container companies (many of which are partly state owned) have made large profits even while seafarers have remained working onboard for months during the crew change crisis.

As the report states, 'the profit margin of ten main container carriers in the second quarter of 2020 was 8.5%, the highest since the third quarter of 2010.'

Flags of convenience

While this support is helping to keep companies afloat and seafarers employed, the report raises questions about whether some of the companies that receive state aid are worthy recipients.

US and European authorities have discouraged granting financial support to companies with links to tax havens. However, flags of convenience mean that many large shipping businesses – in the cruise sector, for example – have made significant profits over the past decade without shouldering the tax burden. Covid-19 state aid is now going to these companies, often through less visible routes. In the UK, this has taken the form of direct grants from central banks.

The failure to attach conditions to state aid is part of an ongoing trend for the maritime industry. For example, while 22 European countries allow a cheap tonnage tax regime, only two have attached environmental requirements for participating companies and only the UK has attached a crew training requirement.

Recommendations

In the event of a continuing Covid economic crisis, or a future pandemic, what steps should governments be taking?

The authors make several recommendations:

- Monitor the sector carefully to make sure that competition is maintained and that markets are not being unfairly distorted in favour of some kinds of shipping company. The ITF identified that state aid in Europe was already having these negative effects before Covid, but there is a danger that the pandemic will make things worse. There is already a high level of consolidation and cooperation in segments of the shipping industry and some regulations make collusion more likely.

- Related to this, shipping competition policy should look beyond the price for the customer to take account of market power vs suppliers and indicators related to service quality, connectivity and environmental performance to make sure that there are further benefits. According to the authors, 'A call for proposals on greening competition policy and state aid recently announced by the European Commission should be used to start greening the EU Maritime State Aid Guidelines, the tonnage tax and the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation. An alternative to widening the scope of shipping competition policy would be to loosen the restrictions on state involvement in companies.'

- Tackle tax avoidance by creating a level playing field in maritime state aid (subsidies and tax exemptions) in different countries. 'A minimum tax for multinational enterprises would eliminate the incentives for tax avoidance and set the bottom for global tax competition.'

- Link aid to the giver's strategic goals, rather than simply trying to mitigate financial losses – for example, the Finnish state aid scheme is aimed at ensuring supply security.

Support with strings attached

All in all, the report concludes, 'State aid… mitigates the negative economic impacts of the crisis on the shipping sector. Yet it also raises questions regarding the stringency of government policies with respect to desired outcomes.' In short, support should come with strings attached.

This is a common criticism, one that has been levelled at governments that have given support to other sectors such as the airline industry, or to the financial sector back in 2008.

The report leaves little doubt that countries could demand more from shipping firms in return for their continuing help. Though the International Transport Forum has focused largely on competition in its recommendations, these demands could relate to flags of convenience, decarbonisation or labour. With the Covid situation set to continue well into next year, it is likely that states will have leverage over shipping companies for some time to come – whether they will use it remains to be seen.

Tags